|

|

Site created

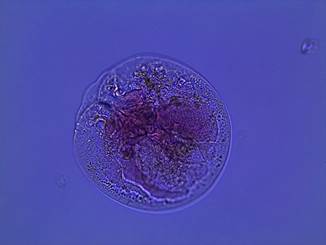

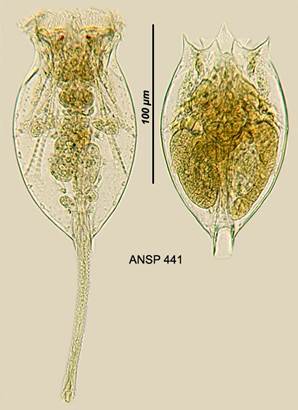

by: Baihleigh Talon Testudinella sp.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Taxonomy Kingdom: Animalia Superphylum: Platyzoa Subclass: Monogononta

Superorder: Gnesiotrocha Order: Flosculariaceae

Family:

Testudinellidae Genus: Testudinella

|

Figure 1: Testudinella sp. Collected from Memorial Pond, 2004. |

Full Known Species List

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Classification

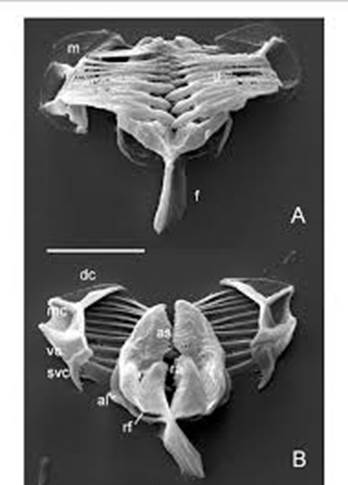

Anatomy Most Testudinella are

characterized by a round, nearly completely circular shaped body. Individuals are capable of retracting both their

ciliated head and foot into their loricae. Testudinella have

two eye spots and distinctive visible musculature. The lorica is

unique in Testudinella in that its ventral and

dorsal plates are completely fused laterally (Glime

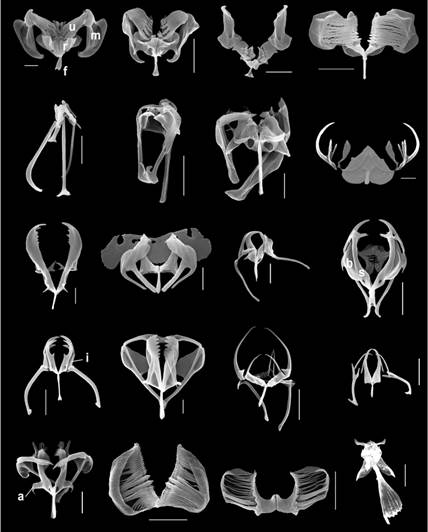

2013). Species differ in morphology

mostly in the shape of the lorica, which varies in

oval, vase-like, and circular forms.

Some species, however, also differ in the length of their foot, which

can be particularly longer or shorter than others. General Body Plan

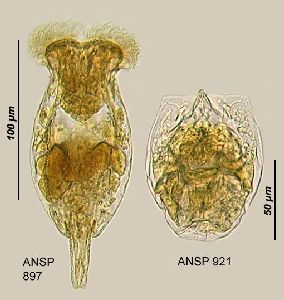

Unlike all other types of rotifers, the foot of Testudinella contains cilia at its end. Figure 2: Testudinella incis,

Pond Collection from Hattingen Felderbachtal,

Germany, 2014.

Trophic Structures

Differences in Body Shape

Between Species

Distribution Species of Testudinella can be

found worldwide. Most inhabit

freshwater lakes and ponds, but eleven species have been isolated in salt

water environments. Five of these

species live exclusively in haline environments,

inhabiting marine and brackish waters.

The remaining species are haloxenous or euryhaline. Testudinella are known to inhabit the benthic, periphytic, and interstitial areas of the water column

(Wei et. al. 2010). Some species are

free-swimming in the littoral zone, where sunlight can reach the sediment

through the water, and where plant life is abundant. They can also be found in sphagnum pools

and among aquatic plants (Glime 2013). Testudinella

patina,

illustrated in Figure 10 above, has been located among arctic mosses in the

Antarctic ocean (Glime 2013). Interestingly, Testudinella patina can also be found in Lake

Erie, of the Great Lakes (GLERL 2015).

Like some species, T. patina has a tolerance for a wide

array of salt levels in its environment (Wei et al. 2010). Feeding Testudinella feed primarily on algae,

bacteria, and debris, using their ciliated corona to pull particles into

their mouths (GLERL 2015). Sometimes Testudinella will sit still, waiting for particles to

pass by, other times they will actively chase after particles, usually in a

spinning movement. The videos below

illustrate their feeding processes. Reproduction As members of the family Monogonata,

most individuals in a population are diploid females, reproducing through

parthenogenesis. Under the influence

of certain stimuli in the environment (possibly overcrowding, poor water

conditions, or food depletion), females will produce females which themselves

produce haploid eggs. These become

males if unfertilized. If fertilized,

however, a diploid, resting egg will be produced. These can remain dormant for some time

until conditions become acceptable again.

Resting eggs give rise to regular, diploid females. Males are significantly smaller than

females, and usually have a much reduced life-span, as their main purpose is

reproduction (GLERL 2015). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works Cited:

Fontaneto, D., Melone, G. and De Smet,

W.H. (2008). Identification key to the genera of marine

rotifers worldwide. MEIOFAUNA MARINA Biodiversity,

morphology and

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||