Zooplankton of the Great Lakes

Zooplankton of the Great Lakes

|

Chirocephalopsis bundyi Classification Kingdom - Animalia Taxonomic History The first identification of Chirocephalopsis bundyi

(fairy shrimp) was in 1876 by S.A. Forbes. In the past, this species

has been listed under the genera Eubranchipus

and Pristicephalus (Dexter 1953).

Anatomy Fairy shrimp are distinct members of the class

Branchiopoda with stalked compound eyes, 11 pairs of swimming appendages, and

a long, cylindrical body without a carapace (Ward and Whipple 1918).

These swimming appendages are used for locomotion, respiration, and food

consumption. Their total length usually ranges from 10 to 18 mm long (Pennak 1953). The coloration in fairy shrimp is variable, but is mostly a whitish color. The first

antennae of this species are relatively small, uniramous, and unsegmented (Pennak 1953). The body of a fairy shrimp is loosely

distinguished as the head and the trunk segments. The trunk segments includes the swimming legs, the genital segments, and the

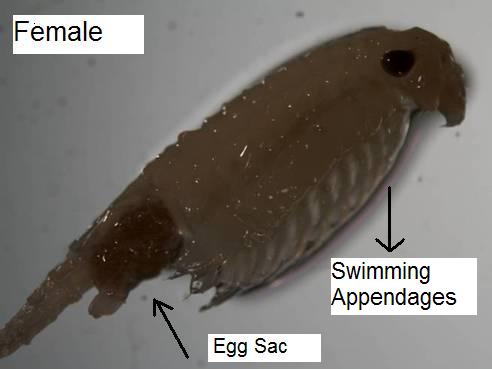

telson with two cercopods (Figure 3). Female fairy shrimp have an elongated,

cylindrical second antennae, while the males have large second antennae

specialized for holding the females during copulation

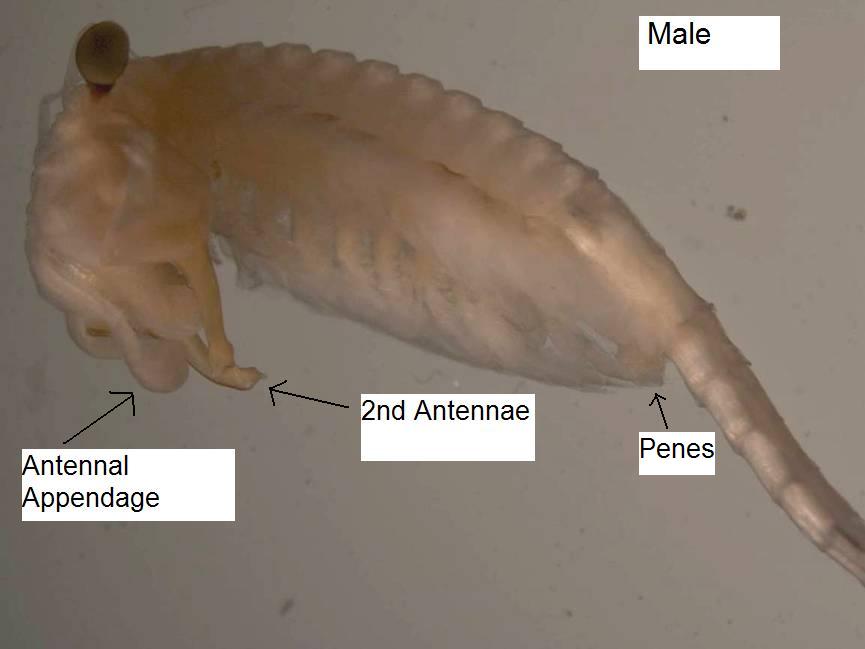

(Pennak 1953). This male species of

fairy shrimp also has an antennal appendage, which

is ribbonlike and coiled close to the second antennae (Figure 1). The

genital segment includes the two penes on the male

and the egg sac on the female (Figures 1 and 2)(Pennak 1953). In addition

the females have a much more compact head and thinner body frame than the

male fairy shrimp. Distribution C. bundyi has been observed in various different localities, but is common in the northern states and

Canada. Some of these locations include Alaska, the Yukon Territory,

Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Massachusetts, New York, Michigan,

Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, and Wyoming (Pennak

1953). The locations of these fairy shrimp are variable from year to

year in distribution and abundance due to favorable conditions (Ward and

Whipple 1918). In most locations, males are less abundant than females.

(Knight et al. 1975). These populations of fairy shrimp are more

abundant in the spring and then disappear in the summer with unfavorable

temperature conditions. C. bundyi is

rarely found in bodies of water that are warmer than 15 degrees Celsius. Habitat Fairy shrimp are

mostly found in temporary ponds or vernal pools. These bodies of water

are usually fishless because they are too temporary, small, and alkaline for

fish populations to survive (Pennak 1953).

Fairy shrimp are absent from lakes and are seldom

found in bodies of water that exceed one acre. These organisms would

not be able to survive with fish as predators, but can usually survive with

amphibians and carnivorous insects, which are other predators of the fairy

shrimp. Also, C. bundyi are restricted

to clear ponds or pools in opposition to other fairy shrimp, which inhabit

more muddy waters (Pennak 1953). Feeding Ecology The fairy shrimp primarily feed on algae,

bacteria, Protozoa, rotifers, and bits of detritus (Pennak

1953). This food is compacted in the ventral groove on a mucilaginous

string located between the bases of the appendages. The available food

is constantly traveling forward to their mouth using the movement of their

appendages (Ward and Whipple 1918). Mastication of their food occurs

right outside the digestive tract in an opening formed by the overhanging

labrum (Pennak 1953). It is believed that

this species feeds continuously, but that not all of

the food is ingested (Pennak 1953). The

primary food for C. bundyi are microscopic organisms and detritus, which they feed on

at the bottom sediment with their ventral side pointed downward (Pennak 1953). Fairy shrimp

are normally found swimming gracefully on their backs with the swimming

appendages faced up toward the light. These organisms frequently rest

on their dorsal side at the bottom sediments (Ward and Whipple 1918). Life History Reproduction requires both the male and female

for C. bundyi since they are not

hermaphroditic. Testes and ovaries are located on either side of the

digestive tract and within the genital segment respectively for males and

females. The males begin by taking a dorsal position to the female with

their second antennae clutched onto the females

genital segment (Pennak 1953). The male will

turn its body at a particular angle to the female so that it can curve its

posterior end and join its genital segment with the external uterine chamber

of the female (Pennak 1953). The process of

copulation only takes a few seconds or minutes, but the pair may stay

together for days before separating. The female carries its eggs in an oval brood

sac for one to several days before being released into the water. The

eggs are released in separate clutches (1-6 total) with anywhere from 10 to

250 eggs per clutch (Pennak 1953). Some of

these eggs become resting eggs as they dry out or are frozen until conditions

are appropriate to hatch. The resting period usually lasts about six to

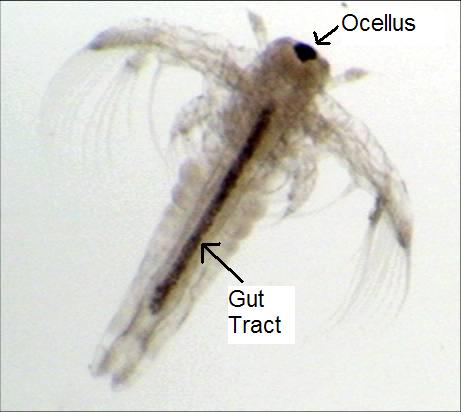

ten months under normal conditions (Pennak 1953). The eggs of fairy shrimp hatch into a naupliar

stage with three pairs of appendages, which will become the first antennae,

second antennae, and mandibles in the adults (Pennak

1953). These nauplii will go through a series of instars where they

will shed their exoskeleton in order to grow.

Throughout these instars, the appendages will increase in number, size, and

complexity (Pennak 1953). At the sixth

instar, all the appendages are present, but it is not until the sixteenth

instar that sexual maturity is achieved (Pennak

1953). Instars for the genus Artemia can be observed in Figures

3, 4, and 5 respectively at days one, three, and five after hatching. Artemia

are from the same order as fairy shrimp and show many similarities in

their physical appearance as nauplii. Literature Cited Dexter, R.W. 1953. Studies on

North American fairy shrimps with the description of two new species.

The American Midland Naturalist 49(3):751-771. Knight, A.W., R.L. Lippson,

and M.A. Simmons. 1975. The effect of temperature on the oxygen

consumption of two species of fairy shrimp. The American Midland

Naturalist 94(1):236-240. Pennak, R.W. 1953. Fresh-water invertebrates of

the United States. The Ronald Press Company. 326-340. Ward, H.B. and G.C. Whipple. 1918.

Fresh-water Biology. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 558-571. |

Figure 1. Male fairy shrimp

with distinguishing ribbon-like antennal appendages and small serrations on

the 2nd antennae. Figure 2. Female fairy shrimp

with a prominent egg sac, 11 pairs of swimming appendages, and a compact

head.

Figure 3. The forked tail or

telson with two cercopods and numerous long

filaments.

Figure 4. Day one

nauplius of Artemia.

Figure 5. Day three

nauplius of Artemia.

Figure 6. Day five

nauplius of Artemia. |